Attorney: Doctor, before you performed the autopsy, did you check for a pulse?

Witness: No.

Attorney: Did you check for a blood pressure?

Witness: No.

Attorney: Did you check for breathing?

Witness: No.

Attorney: So then, is it possible that the patient was alive when you began the autopsy?

Witness: No.

Attorney: How can you be so sure, Doctor?

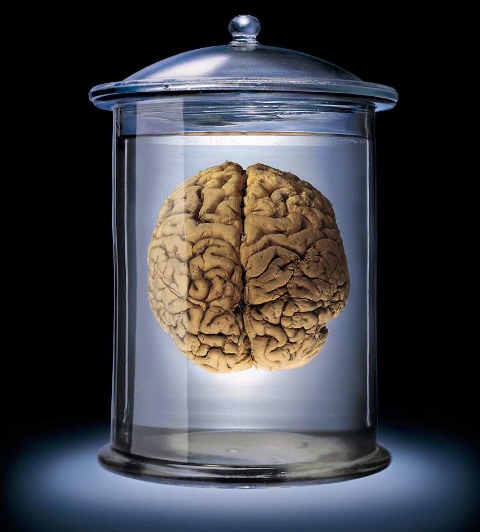

Witness: Because his brain was sitting on my desk in a jar.

Attorney: But could the patient still have been alive, nevertheless?

Witness: It is possible that he could have been alive and practicing law somewhere.

Courtroom exchange between an attorney and a witness, as reported in the Massachusetts Bar Association Lawyers’ Journal[1]

During a physician’s career, it is likely that he will be named in a malpractice action. Before the trial, any party in the action is allowed to take sworn testimony of any witness, opposing party, or any expert expected to testify at trial for the opposition. The witness will be placed under oath to tell the truth and then the lawyers from each party will be allowed, in turn, to ask questions. This pre-trial testimony is called a deposition.

The conduct of a deposition is very structured; the lawyers know the rules but the physicians, and other witnesses generally do not. Being forced to answer questions by an adversarial attorney while you are under oath can be stressful. It can be especially unnerving to be limited to only answering “yes” or “no” when you really have more to say; but you must play by the rules of the court. Although stressful, knowledge about the proceeding and awareness of trial strategy can make it tolerable and perhaps, allow you to perform with more confidence.

As a discovery tool, the deposition is useful to gain information that may not be in the medical records, obtain useful admissions from the witness, and box the witness in as to what he can say at the trial. It is common for the attorney to close his questioning by asking the witness if there are any other issues he will testify to at trial. If the witness says “no” then he will not be allowed to bring up new issues at the trial unless the opposing attorney “opens the door” to new testimony by asking a question that is beyond the scope of what was asked at the deposition.

There is no judge present at the deposition so any objections to a question will have to be ruled on at a later time. What usually happens is the objecting attorney will place the objection with a short legal reason which should give the questioning attorney a clue as to how to correct the question so that it will no longer be objectionable. Usually the asking attorney will change the question to pass muster, but he does not have to. The witness must answer the question unless his attorney claims the answer is protected under some privilege e.g., attorney-client or husband-wife. If the judge later sustains the objection, the answer given will not be allowed to be used at the trial.

If an attorney makes an objection to a question, he may only make it as to the form of the question; he may not make a “speaking” objection as that would give the witness a clue as to how his lawyer would like it to be answered. For example, the objecting attorney may tell the witness to answer only if he remembers or if he knows. This type of objection would never be allowed at trial so it is not allowed at a deposition, also. In fact, there are rules that make speaking objections subject to sanctions. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Federal Rule 30(d)(2) states, “[t]he court may impose an appropriate sanction—including reasonable expenses and attorney’s fees incurred by any party—on a person who impedes, delays, or frustrates the fair examination of the deponent.”

The questions and answers at the deposition will be recorded by a court reporter and the transcript of the proceeding will be given to either party provided they pay the fee for the transcript. Some depositions are video-recorded. This video may be used at trial if, for some reason, the witness is not able to attend. This video would be more effective than just having someone get on the stand and read the answers to the jury. The jury will be able to evaluate the witness’s demeanor, the tone of voice and the timing of the answers so as to get a better feel as to credibility.

Depositions are a great opportunity for an attorney to learn about the adversary’s case and get a feel for the performance and credibility of the witness. Although a majority of medical malpractice cases get resolved before they ever get to trial, it is rare for the resolution to occur before the depositions of the plaintiff, defendant, and plaintiff’s expert. If the plaintiff’s expert isn’t knowledgeable and credible, it is unlikely that plaintiff’s attorney will take the case to trial; he may try instead, to push for a settlement.

There is a great deal of strategy that goes into taking depositions. Many experienced lawyers will try to get right to the heart of the matter and ask as few questions as possible to get the information they need to support their theory of the case. This “short and sweet” approach is possibly due to the fact that the witness, if it is an expert for the opposition, must be paid by the deposing attorney’s side. Also, many attorneys are busy and don’t want to waste time by eliciting unhelpful testimony.

Some attorneys have a different strategy. They will drag a deposition on for hours in hopes of tiring the witness out. They will then try to trap the witness into saying something harmful to the case which he would never say if he was not worn out and “unalert”.

If you are the one being deposed, your behavior is very important. You must do your best to answer the questions honestly. Do not interrupt the deposing attorney until he has finished asking the question and then wait a few seconds to give your attorney a chance to object if he needs to. Even if your attorney objects to a question, you must answer to the best of your ability unless a privilege is invoked; if this happens, your attorney will instruct you to not answer and he will let the deposing attorney know the grounds on which he is objecting. They may argue a bit and they may even have to get the judge on the phone for a ruling. Your job is to sit tight and watch the drama unfold in front of you.

In general, the deponent is not allowed to confer with his attorney during the course of the deposition. This rule has gotten some criticism as a denial of the right to counsel especially if there is a prolonged break in the questioning. Because of this criticism, most courts agree that you, as deponent, and your counsel can confer during a recess, but there should be no coaching as to how to answer the questions. Once back on the record, do not be surprised if the questioning attorney asks you what you and your attorney discussed during the break. He is allowed to ask these questions to see if any improper coaching occurred; you must answer the questions so it is best not to put your attorney into a bind by asking him for help during the break. Once you are on the stand, as in court, you are on your own until the attorneys have finished with you.

Always be professional. You’re a doctor; use a professional demeanor. Be polite. A deposition is stressful but it is best to maintain your cool and answer to the best of your ability. The jury knows that your are stressed and they will respect you more if they see you are being polite—even to your adversary. Dress appropriately.

If you are asked a question and you don’t remember the answer, it is acceptable to say that you “don’t remember” or “don’t recall.” It is the rare individual who can recall what he was thinking at a particular time many years ago. It is not a good idea to guess at what you could have been thinking. The opposing attorney may ask you to look at the medical records and then ask if you can come up with the answer. If the chart review does not help you remember then say so.

The opposing attorney may present you with a hypothetical patient who is similar to the plaintiff and then ask for your opinions as to diagnosis and treatment. As a physician, it is fair for you to point out that the presence of the patient (one that you can actually talk to and examine) is critical to making a diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan. It is fair to be reluctant to give a definitive answer based on limited knowledge.

If your case involves a missed diagnosis which led to harm to the patient, some attorneys will persist in trying to get you to admit to a mistake. They will do this by posing a theoretical question dealing with the signs and symptoms of the patient and ask you to provide a differential diagnosis. For example, let’s say the patient had an aortic dissection and the diagnosis was not made until the patient was already dead. The attorney might ask for a differential diagnosis for a patient who presents with substernal chest pain, shortness of breath, and tachycardia.

Faced with this scenario, the inclination is to say, “It could be an aortic dissection.” This is especially true in light of the fact that you already know that is what the patient had. It would be truthful and better for your case if you don’t jump ahead. Provide the attorney with a list of conditions that meet the proposed criteria so that the jury can actually see that the case is not as simple as the plaintiff is trying to portray. In this example, the list could include myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus, aortic dissection, pneumonia, pancreatitis, a duodenal or gastric ulcer with perforation, costochondritis, and perhaps a sternal or rib fracture. There are other possible diagnoses you could add but I think you get my point.

Remember to only answer the question that you have been asked. Many defendants feel that giving a long, detailed explanation that goes beyond the scope of the question will educate the attorney as to your thought process and make him realize that you are a knowledgeable, reasonable, and prudent physician. This is unlikely to happen and you may even be hurting your case. Actually, the more information that you provide to the plaintiff’s attorney will just provide him with more material with which to ask you questions.

So if you are asked a “yes” or “no” question, you do not need to provide any explanations. For example, if you are asked if you remember seeing the patient on a particular day when there is no note by you or your team and you really do not remember, then “no” is the answer. If you say, “No, but it could have been one or two times and I just didn’t document it,” you will be opening yourself up to another line of questioning dealing with your documentation habits.

In a deposition, the intent of your attorney may not be to educate the jury. He may prefer to wait for the trial to do that. He may advise you to use medical terms in your answer so as to force the deposing attorney to look to you for help. This may not be the best strategy especially if your testimony ends up being read back at trial, but you will need to follow your attorney’s advice. I prefer to answer in a way that would be understandable to a lay person. If your deposition testimony is being read to the jury at the trial, they may not appreciate it if they think you are talking down to them.

Do not try to be funny or sarcastic with the opposing attorney. Every word you say is being recorded by the reporter and it may not sound very good if the transcript is read back to a jury at trial.

It is unlikely that a clever response on your part will end up in the next edition of Foolish Words.

[1] Ward, Laura: Foolish Words, The most stupid words ever spoken, PRC Publishing Limited, New York, 2003, p.120.

by Darryl S. Weiman, M.D., J.D.

Professor, Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Tennessee Health Science Center and Chief of Surgery, VAMC Memphis, TN

MORE ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Darryl Weiman is a featured expert in www.healthcaredive.com on February 17, 2016.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog andd wished to say that I

have really enjoyed surffing around youur blog posts.

After all I will be subscribing too your feed

and I hope you write again very soon!